How philanthropy can help the world build back better

Last year, COVID-19 pushed an estimated 71 million people into extreme poverty and kept 90 per cent of all students worldwide out of schools – with 500 million not having access to remote learning.

Such devastating effects of the pandemic have disrupted the world in its mission to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, said the former Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN), Mr Ban Ki-moon. The SDGs, mapped out by the UN in 2015, include ending poverty, improving health and education, and controlling global warming.

Highlighting the need to do more, he said, “Certainly, it has shown us the role and impact philanthropy must play in helping us to bridge the gap in our efforts to achieve the SDGs.”

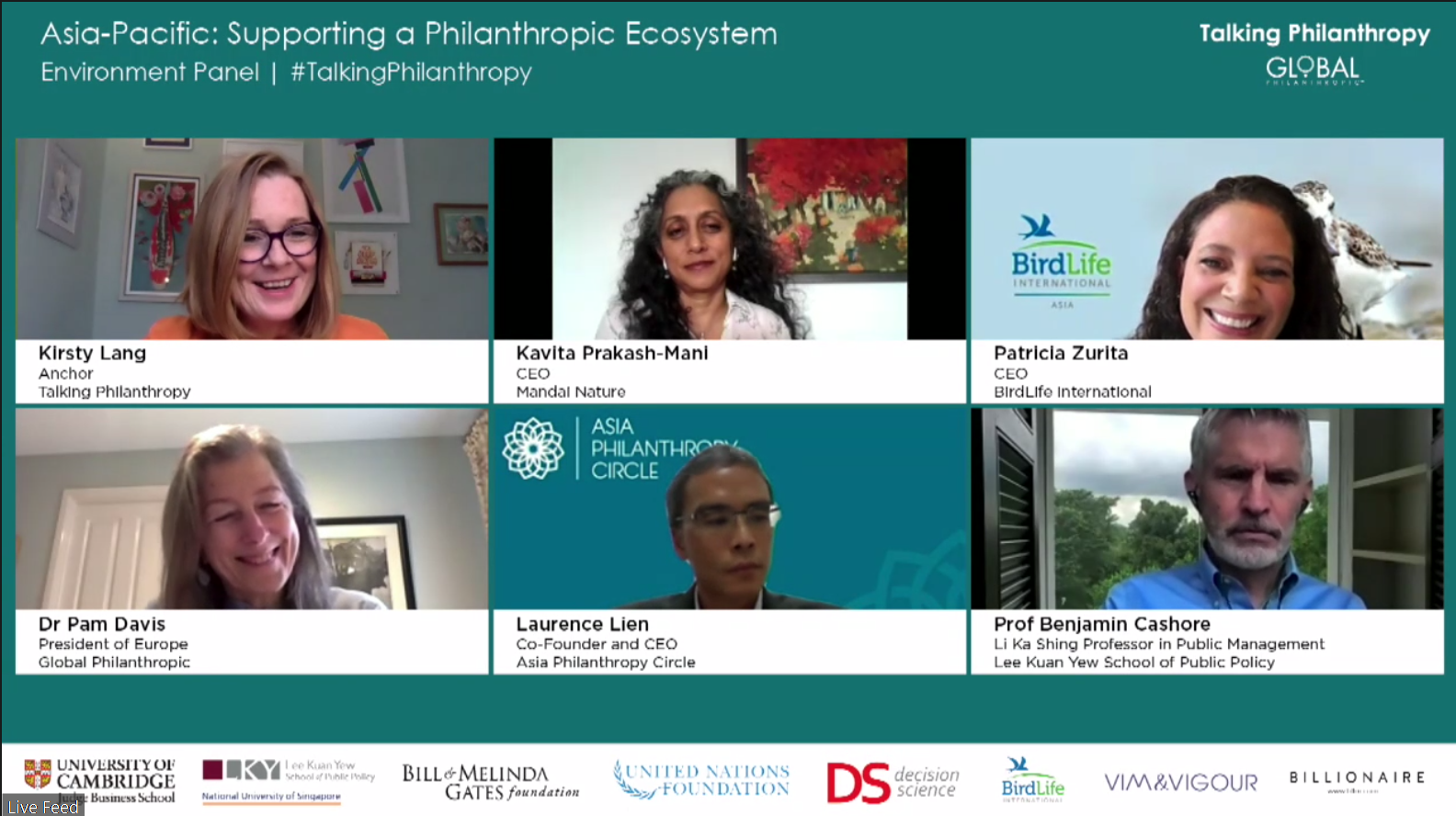

Mr Ban was the keynote speaker at Talking Philanthropy, a virtual forum co-hosted on 14 May by Global Philanthropic, the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at NUS (LKY School), and Cambridge Judge Business School.

Describing philanthropic organisations as “essential partners”, he urged forum participants to advance philanthropy, in particular in the Asia-Pacific region, and press on with interventions needed by governments to foster philanthropy.

Echoing the focus on the Asia-Pacific, NUS President Professor Tan Eng Chye said the region is unique as it is both rich and poor at the same time. It has more high-net-worth individuals than elsewhere, and is home to the biggest and fastest growing industry giants.

“Yet, it is also a region with many pressing and diverse needs where over 400 million people are living in extreme poverty and abject conditions,” said Prof Tan, who gave the opening address at the forum that sought to support a philanthropic ecosystem in the Asia-Pacific.

“There is real opportunity for philanthropy to reach, shape and impact the lives and futures of disadvantaged communities in Asia.”

The forum went on to discuss several issues that are critical for the survival of humanity, especially the environment and health.

Overlooking the environment

While climate change is a major concern, less than 2 per cent of global philanthropy is directed to climate causes, of which only half goes to Asia.

Experts on the environment panel cited several reasons for this incongruity, including a lack of awareness of how the environment impacts health, and the fact that it seems too big an issue to tackle.

Birdlife International Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Patricia Zurita explained how people see haze but do not associate forest loss, caused by the slash-and-burn method of cultivation, with health problems.

Neither do they connect conservation to the prevention of pandemics like COVID-19, as the virus is suspected to have originated from animals, she added.

Others find environmental issues like climate change too overwhelming, said Mr Laurence Lien, Co-Founder and CEO of Asia Philanthropy Circle.

“It is not like addressing the education or health needs of a poor child, where you can see immediately what you can do. But with climate change, it is more long-term,” he said.

“It is easy for people to just give that excuse, ‘Let the government take care of this, (as) we can’t play a meaningful role’.”

Glimmers of hope

Despite the obstacles to environmental action, there are encouraging signs that people are concerned, said Professor Benjamin Cashore of the LKY School.

He gave the example of foundations from other parts of the world turning their attention to the region, such as through the Climate and Land Use Alliance that tackles deforestation in Southeast Asia to mitigate climate change.

“It isn't just the question of the need to think about directing the funds, but also how and where to direct the funds,” he said, adding that there is growing interest from philanthropists, the private sector and governments in addressing the climate crisis.

When asked by moderator Ms Kirsty Lang of Talking Philanthropy on lessons learnt from his deforestation research, a topic that generally receives a lot of philanthropic funds, Prof Cashore emphasised the importance of creating durable policy tools that lead to results and inspire funding.

Using his research into eco-labels as an example, he said that encouraging responsible commercial practices and engaging stakeholders are not strong enough to make a real impact on reducing deforestation. The solution is the sustainability of right policies.

“Think of the problem you want to solve, and the durability of that policy tool,” he said. “We have no time to learn from short term results for long term problems.”

Tackling the coronavirus and ageing

Unlike the environment, the health sector has had no shortage of interest from philanthropists, especially during the pandemic.

Today, a lot of attention is being placed on vaccine research, immune response and the epidemiological aspects of managing a pandemic such as safe distancing measures.

In fact, philanthropy has played a big part in Singapore’s healthcare history. For instance, NUS was started about 115 years ago with the establishment of a medical school following a public appeal for funds led by local businessman and philanthropist Mr Tan Jiak Kim, said Professor Chong Yap Seng, Dean of the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine).

NUS Medicine has since given back to society, most recently playing a major role in responding to the pandemic. Faculty members, who are also doctors, cared for COVID-19 patients and volunteered to man stations in migrant worker dormitories when there were outbreaks last year.

The School’s research also contributes to achieving the third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3), which is to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages. Prof Chong said it has research programmes that focus on human potential, which helps babies get the best start to life, as well as looks at extending the healthy lifespan of individuals.

“In Singapore, we have one of the longest life expectancies at about 84 years old, but the healthy lifespan is about 74. There is a 10-year gap. We hope to reduce the gap by two to three years, and eventually five years,” he said.

Sustaining philanthropy into the future

Prof Chong believes that research into philanthropy is also needed. Noting that the younger generation is more socially conscious, he said, “It would be useful to know more about what purposes would speak most to these generations.”

Wrapping up the forum, LKY School Dean Professor Danny Quah said he went into the sessions with a big question – why is it so hard for philanthropy to change the world for the better? And he went away with two key points.

“When there is a single clear goal and an immediacy, and where transactions, even micro-transactions, are made convenient, (philanthropy) will happen. It will happen very quickly,” said Prof Quah.

His second takeaway is that philanthropy is not transactional. “It isn’t about consumption, where a philanthropist walks into a store and points to a pizza and says, ‘I want that pizza, here’s my money’. It is about an investment relationship,” he said.

While there is a range of professionals and services that aid financial investing, such as risk analysts and strategic consultancies, there are few that target philanthropy. “That is an ecosystem that we need to build in philanthropy,” he said.